The following article was taken from The Institute For Creation Research (ICR)

Studies Show Extinct Reptiles Moved with Grace and Ease

by Brian Thomas, M.S. *“Scientists have struggled for decades to figure out how giant pterosaurs could become airborne and some recent proposals have simply assumed it must have been impossible,” according to Michael Habib of Chatham University USA.1 He recently co-authored a new study on pterosaur flight, the findings of which show that these giant reptiles not only could fly, but could do so skillfully.

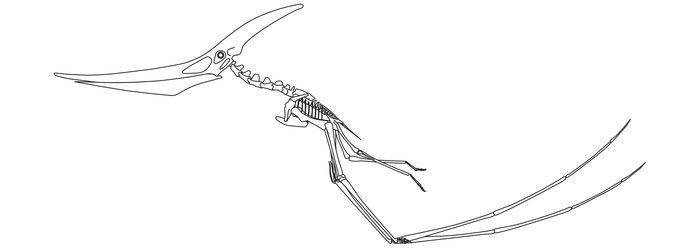

Pterosaurs were the largest known flying creatures. Based on their fossils, their estimated total wingspan reached almost 40 feet. Habib and Mark Witton of the University of Portsmouth investigated pterosaur bone structure, estimated the reptile’s weight and musculature, and modeled its flight dynamics.

Based on their results, they concluded that pterosaurs could launch themselves with a “pole-vaulting” maneuver, fly, and land with agility—even those that were large enough to look a giraffe in the eye. Witton told Canada’s CBC radio program As it Happens, “We found in every avenue of investigation that we went down, the evidence pointed towards [pterosaurs] being flighted.”2

So, it appears that these flying reptiles were not large and ungainly, but large and graceful—as would be expected if they had been intentionally created to fly.

This study parallels other fossil finds that demonstrate that large extinct animals moved with ease. For years, researchers doubted that large theropods like Tyrannosaurus rex would have been able to effectively maneuver their bulky bodies. In a study published in The Anatomical Record, W. Scott Persons IV and Philip Currie examined points on T. rex tail bones where the largest locomotive muscles would have attached.3

When compared to living lizards and to an anatomical torque and force model, these scientists observed that T. rex leg muscles would have been very robust, easily able to propel and maneuver the giant land walker. In addition, the same skeletal features, including specified sizes and shapes of vertebral and rib features, are common to all theropods.

The study’s authors, interpreting their results according to evolution, wrote, “Dorsally elevated transverse processes [vertebral features] are characteristic of even primitive theropods and suggest that a large M. caudofemoralis [tail-leg muscle] is a basal characteristic of the group.”3 In other words, since all theropods had bony and muscular features enabling efficient movement, these features must have evolved very early.

However, there is no evidence of such evolution! There are no examples of pre-theropod fossil skeletal features that show any hint of transitioning toward the observed fully developed theropod-like features. Therefore, it looks as though all theropods, including T. rex, were created with the fully formed ability to move with agility, just like pterosaurs were created to fly gracefully and mosasaurs were created to be expert swimmers.4

When researchers have tried to piece together the past, the assumption of evolution has led to wrong conclusions. Most fossils are broken and fragmented, making reconstructions difficult. But by reasoning that all creatures “emerged” from a lesser form, evolutionists have been “seeing” what is not really there: incomplete, ineffective, and substandard transitional body plans. In each case mentioned here, however, anatomically rigorous investigations have shown fully featured creatures.

These fossils show no trace of evolution. Instead, they show the kind of well-thought-out design that researchers would expect to find if the animals had been created on purpose with the exact characteristics needed for their own particular environments.

I never thought of the Cockatrice as a Pterosaur; what an awesome thought! Love the info on how well designed these creatures were. 🙂